Friday, October 20, 2017

Roos, Astros, and a Texas World Series Title

Texas baseball was born in Houston, but it was raised in Sherman.

The first recorded baseball game in the state of Texas took place April 21, 1867. On the 31st anniversary of the Battle of San Jacinto, a local Houston club defeated a visiting Galveston team on the actual battlefield just east of Houston. Former Austin College trustee Sam Houston, an opponent of the Civil War, had passed away just four years earlier. Sam Houston wasn’t the only Texan in opposition to the war. Grayson county had voted against secession as well.

Baseball was a Yankee game, born around New York in the 1840s. Southern soldiers were first introduced to the game during the war, and brought the sport back home after 1865. Hostile, pro-secession areas of the south did so only reluctantly. Places like Grayson county, filled with more ambivalent Midwesterners, embraced this new sport with passion.

Veteran and Sherman resident Charles Batsell returned home from the war, made his fortune, and established a baseball park for the community. Batsell’s park was a permanent fixture in Sherman, and was eventually used for Austin College’s first football game against Texas A&M in 1896. But before that year, Batsell’s park was a home for the growing sport of baseball.

Professional baseball in Houston was born in 1888 with the establishment of the Houston Buffaloes franchise within the first Texas League. The first league was initially comprised of just the largest cities in the state (Houston, Dallas, Austin, San Antonio), struggled, and folded in 1892. The problem was “the jump”, the high costs associated with long travel. By 1895, Texas baseball proponents had a cost-cutting solution: a new Texas League divided between North and South.

The Texas League southern division included Houston, Galveston, Austin & San Antonio. The northern division? Dallas, Fort Worth, Waco, and……….. Sherman, TX. Such was the popularity of Grayson County baseball that league officials considered Sherman worthy of games against the larger cities in the state. Officials in Grayson county successfully argued for Texas League inclusion by pointing to Batsell’s park, high school teams, numerous club teams, and an unofficial team at Austin College.

The Sherman Orphans opened up the 1895 season with wins against Dallas and Fort Worth, and later in the season departed for Houston to take on the Buffaloes. The 1895 Dallas team was owned by Sherman enthusiast Ted Sullivan, who had “discovered” Charles Comiskey and later coined the term “fan” to describe sports enthusiasts. The 1895 Houston Buffaloes squad included sluggers such as Ollie Pickering, whose propensity to turn bloopers into hits eventually led to his teammates referring to them as “Texas Leaguers”. The success of minor league baseball in Sherman helped other teams in Northeast Texas establish their own franchises years later.

The star pitcher of the 1895 Sherman Orphans was a local kid named Cy Mulkey. He was a Texas League journeyman who by 1899 was pitching for the Houston Buffaloes. By 1902, Mulkey was a manager in Corsicana, and became a part of baseball history. When the Corsicana owner demanded Mulkey allow his entitled and inexperienced son to pitch over Mulkey’s objections, the Shermanite started the son and refused to pull him. As Texarkana cruised to a 51-3 victory, Mulkey famously shouted to the team: "His daddy said he's going to pitch, and he's sure pitching, ain't he?" The 48-run loss is still today the worst loss in professional baseball history.

By 1907, Mulkey was done with the Texas League. He headed back home, to manage the Austin College baseball team. At AC, Mulkey presided over a Roo Renaissance on the diamond. His arrival coincided with Austin College’s entry into the TIAA along with the top schools in the state. AC recruited some of the top players in Texas during this era. One of those players was a pitcher named Alex Malloy. In 1908, Malloy and the Roos faced Christy Mathewson and the New York Giants in Sherman during Giants spring training. Roo opponents that year included TCU, A&M, and UT. In 1909, Malloy led AC down to Austin and defeated the Longhorns 5-1. The Kangaroos would defeat UT in subsequent years without Malloy; by then he was already headed for greener pastures.

In the summer of 1909, Malloy was signed by the Houston Buffaloes. His performance in Houston was so strong that year that he began to attract the focus of Big League scouts. The St. Louis Browns were particularly interested, and called up Malloy during the summer of 1910 for the remainder of the season. The highlight of Malloy’s one year in the major leagues came at Sportsman’s Park in St. Louis on September 25, 1910.

Malloy got that call that day on the mound against the Washington Senators. His opponent just happened to be the best pitcher in the history of baseball, Walter Johnson. Johnson was untouchable. He struck out 11 Browns in a 1-hit complete game shutout. His 11 strikeouts got him to within 4 Ks of the all-time single season strikeout record, and he’d surpass that record on his next start. Washington won, 3-0.

But the Roo was up to the task. Malloy also went the distance, striking out 7 and allowing only 6 hits. According to the Washington Herald:

“Malloy, who opposed Johnson, pitched very fair ball, and had he distributed the half dozen hits gathered by Washington a little more effectively, there is a possibility that the teams might have fought on indefinitely without a decision. Malloy forced seven Nationals to strike out – not a bad record for a recruit.”

Today, Walter Johnson is 4th all-time in career complete games (531), second in wins (417), and first in shutouts (110). He was the all-time career strikeout leader with 3,508, until he was passed much later by a Texas native playing for Houston.

Malloy would return to the minors for another 4 years after 1910, and finished his career with the Houston Buffaloes. He was on the roster in 1914, when the Buffaloes met the New York Yankees during spring training at West End Park in Houston. The Park was located in downtown Houston, not far from Minute Maid field. The 1914 Yankee – Buffalo game is known for a famous photo of a home plate slide.

The Houston Buffaloes became the first official farm club of a major league franchise in the 1920s, when the team established a relationship with the St. Louis Cardinals. They were playing good baseball at West End Park that decade, and they were playing good baseball not too far away either. Rice baseball was led by a star SWC pitcher named Eddie Dyer, and was managed by Austin College legend Pete Cawthon. After graduation, Dyer was signed by the Houston Buffaloes, and was later called up to the Majors by the Cardinals. Dyer spent the year 1926 assisting Austin College athletics with Coach Cawthon, and helping St. Louis win the World Series. The town of Sherman threw a parade in his honor that year, and declared the day “Eddie Dyer Day.”

A managerial career within the Cardinals farm system followed Dyer’s playing days, and he skippered the Houston Buffaloes to three first place finishes and one Texas League championship in 1940. This success earned him the manager job of the St. Louis Cardinals in 1946, and Dyer promptly led St. Louis to another World Series title exactly 20 years after his title as a player. The 1946 Series against the Boston Red Sox went 7 games. Enos Slaughter’s “mad dash” gave St. Louis a lead in the eighth, but Boston threatened to tie in the ninth. Down one run with two outs and two on, up to the plate walked Austin College Kangaroo Tom McBride. Former Austin College coach Eddie Dyer walked up to the mound to have a conversation with his relief pitcher, who successfully got a McBride ground out to end the Series. The Red Sox curse would continue for another 58 years after this disappointing loss on the same field where Alex Malloy and Walter Johnson had gone head-to-head.

The city of Houston petitioned for a Major League team for most of the post WW2 years, and the big break finally came in 1962. A group of Houston entrepreneurs received permission for a franchise, if and only if an agreement could be reached with the Houston Buffaloes. Eventually a deal was made, assets, staff, and coaches were transferred to the new Houston team, and the era of big league baseball by the Buffalo Bayou was born.

There have been many highlights since. The eighth wonder of the world was built in 1965. Texas native Nolan Ryan passed Walter Johnson’s career strikeout record as an Astro, and threw a major league record 5th no-hitter in the Astrodome. Mike Scott clinched a division title with a no-hitter. Bagwell, Biggio, & Berkman were one long highlight film. Roos my age are familiar with the thrill and ultimate frustration of 1980 and 1986. Younger Roos can recall the excitement of 2004 and 2005, and the exasperation of that first World Series loss to the White Sox.

We’ve seen losing streaks miraculously end in over the past 13 years. The Red Sox, the White Sox, and the Cubs have all snapped their skids and have brought home championships. In some ways, the longest losing streak in Major League baseball today is……the state of Texas. The Rangers and the Astros have played 113 seasons with zero titles to show for it. That will end one day.

The Yankees that squared off against the Houston Buffaloes in 1914 are now up 3-2 against Houston as the ALCS returns to Texas. But I still believe. Just two wins, and Houston finds itself in the World Series for a second time. It’s been a long and winding road since that day on the San Jacinto battlefield and through the efforts of Mulkey, Malloy, & Dyer, as well as Ryan, Biggio and Verlander. In fact, it’s been exactly 150 years. And maybe a celebration of the sesquicentennial of Texas baseball is just what is needed to finally bring a World Series title to the state of Texas.

150 years is a long time. Heck, it’s almost as old as Austin College itself. Almost.

Go Astros! Beat the Yankees and bring home a title. Let’s do this Houston and Texas.

Wednesday, October 11, 2017

Athens and Austin College: A Texas Hoosiers Tale

According to the Houston Post, the Roos “put up a plucky fight” in their football contest against TCU in late October 1909. But the Horned Frogs eventually prevailed by a score of 18-3. Austin College boarded the train to head back to Sherman. Soon, Waco was disappearing in the distance.

Wait, what? Waco?

Yes, Waco. Before TCU’s move to Fort Worth in 1910, the school was located in Waco, TX. West Waco to be exact. East Waco was the home of their rival Baylor. The "Revivalry" was initially an all-McLennan County affair.

One month later, TCU made the short trip east to take on the Bears during Thanksgiving week. Baylor furnished special trains to bring thousands of alumni back to campus. Parades were organized. The Baylor band performed “The Homecomers March”, and the Bears barely defeated TCU 6-3.

It was the first ever Homecoming in this nation’s history.

It’s Homecoming weekend in Sherman, TX. All of this writing has been something of a Homecoming for me already. I’ve immensely enjoyed meeting many of you both online and in person, and am looking forward to more of the same. I am excited to see many of you on campus this weekend, and if not at some future event. I hope the writing has filled you with the same amount of pride and enjoyment that it has for me.

Today’s Roo Tale was voted on by the Go Roos Facebook group earlier this fall. It’s a Texas Hoosiers tale, about the near impossible things that can be accomplished by smaller schools against their larger competitors. It focuses on the spectacular basketball accomplishments of little Athens, TX, and the Roo who helped to make it happen. It mentions this same Roo’s efforts in establishing a Coaches Association in Texas that now includes tens of thousands of members. And it features supporting actor roles by two AC icons, Coach Ralph “Slats” McCord and Coach Bob Mason.

And it’s a story about coming home. See you at Homecoming.

Chapter 1: "Didn't know they grew 'em so small on the farm"

The relentless northward growth of the Dallas / Fort Worth metroplex over the past 100 years has transformed small towns in Collin County into bustling cities in their own right. Little Celina, TX is no different. The town of a few hundred residents was not even incorporated when little John Taylor Nelson was born in 1905.

Nelson was a standout athlete at Celina High School. He participated in football, baseball, and track. But his first love was basketball. As luck would have it, Celina was a basketball town. Nelson helped guide Celina to the state tournament in the early 1920s, and revenue from the sport actually assisted the early days of Celina football.

Celina lies halfway between Austin College and SMU, and Nelson’s high school days coincided with the height of the Kangaroo-Mustang rivalry. AC beat SMU three out of four times in football while Nelson competed for Celina, and the Roos beat the Mustangs in basketball his senior year of 1923.

Although still young, Dallas was quickly propelling SMU towards athletic success by luring some of the best athletes in the state. The Mustangs’ first star was a local boy named Jimmy Kitts. At SMU, Kitts excelled in football, baseball, and basketball, and earned All-American honors. Kitts was the SMU QB when his Mustangs fell to AC 17-7 at Fair Park Stadium in 1921. His career included more than a few trips to Sherman, and many of those contests were attended by Nelson himself.

Because of the influence of Kitts, Nelson considered SMU in 1923. However, AC had just hired the already well known Pete Cawthon, coach at Terrill Prep (now St. Mark’s) in Dallas. Cawthon’s Terrill boys were committed to following their coach to Sherman, and the idea of being a part of something new and exciting was too much. Nelson decided he would join them and become a Roo. As Nelson headed to Grayson county instead of Dallas county, his Celina teammates held a party to wish John Taylor well. Nobody called him John Taylor though. Everyone referred to him by his old Celina nickname: “Bobo”.

At Sherman, Bobo Nelson was a four sport star. He was a member of Cawthon’s 1923 TIAA championship team, and was a contributor in AC’s 7-3 upset of Baylor in Waco. He starred on the diamond, and was a speedster on the track. But his main contributions to AC athletics were on the basketball court.

The golden era of AC athletics in the 1920s included basketball. Nelson and the 1924 Roos had a strong season, defeating SMU, TCU, and eventual TIAA champion Southwestern. He was a starter all four years. In his senior season of 1927, the Roos made a run at the TIAA title and fell just short. That same year, AC defeated East Texas State down the road in Commerce. It was a victory over an Austin College rival that would not be seen again for decades.

While Nelson was shining against schools like SMU, Mustang Jimmy Kitts had moved on to coaching at the University of Dallas. There, he became friends with arguably the most famous Roo athlete of all, Cecil Grigg. Grigg had ties with the University of Dallas after his AC playing days, and at the time was an NFL star alongside Jim Thorpe with the Canton Bulldogs. Kitts persuaded Grigg and fellow professionals to participate in a football game exhibition with the University of Dallas in downtown Dallas. As reported by the Post, "Jimmy Kitts, former SMU captain, and Cecil Grigg, who is perhaps the greatest athlete Austin College ever produced, played vigorous football."

The two became close friends because of the experience, and would be reunited later. For Jimmy Kitts, there would be no escaping the influence of that school in Sherman.

Chapter 2: "I'm sure going to the state finals is beyond your wildest dreams, so let's just keep it right there."

High school football exploded in popularity in East Texas during the 1920s. Every town from Dallas to the Sabine river dreamed of gridiron glory, and many achieved it. Tyler, Marshall, and Corsicana became famous for their success.

But little Athens, TX struggled. Try as they might, the Athens Hornets consistently failed to make the playoffs. When that goal was accomplished, Athens nemesis Marshall was always there to send the Hornets home for good.

Athens never stopped trying to overcome that hurdle. But like a wise investor deciding not to put all of one’s eggs into the same basket, the Henderson county town also began to dedicate itself to a different sport.

As the 1920s progressed, basketball became the sport of choice around which the Athens community gathered. Families of players from rural Henderson county were encouraged to move into town. Youngsters were as likely to practice their free throws as they were to put on a leather helmet. And Athens was focused on landing a star coach that would lead them to glory in the gymnasium that had eluded them on the football field.

The population of Athens was roughly 3,000 in 1920. Dallas, Houston, & Austin were well over 100,000. Even mid-sized towns such as Waco were over 10 times the size of Athens. At that time, all 200+ schools in the state of Texas completed in one classification, Class A, for a state championship in football, basketball and baseball.

For a small school to win a championship, something along the lines of a Milan miracle would be necessary. Tiny Milan High School won the Indiana High School state championship in 1954, and became the inspiration for the movie “Hoosiers”. In 1925, Athens believed they had found their version of Hoosier Coach Norman Dale. Jimmie Kitts was lured away from the University of Dallas to coach the sport he loved.

Basketball in the 1920s was different compared to today. It was slower and shorter. The game clock never stopped, and there was no shot clock. The games lasted for only four 10-minute quarters, and there was no 10-second midcourt rule. Low scores were common, as was stalling. Kitts was an innovator who refined the game in Athens. Hook shots were introduced on the offensive side; double teams were a new feature on defense. The 1925 Athens team showed immediate promise under Kitts, and the 1926 team was a state power. There was excitement and anticipation in 1927.

Nacogdoches fell on the way to a district championship. Athens cruised through regionals, defeating Huntsville and earning a trip to the state tournament. Because of construction in Austin, the state tournament was held at DeWare Field House in College Station. There, Athens rolled up wins against Shiner and Cisco to reach the finals against Denton High School.

Hundreds traveled to College Station to watch the game. Those who could not make the trip were kept up-to-date via the telephone. Down by two points at the half, star Jake Reynolds and the Hornets came out firing and coasted to a 23-14 win. Little Athens Texas was the best basketball team in the state. The team arrived back home in Athens for a celebration at the courthouse.

Before departing for home, Kitts received a telegram. His Hornets had been invited to play in Amos Alonzo Stagg’s National High School basketball tournament in Chicago later that spring. Stagg, famous for his late 1890s Chicago Maroons football teams, had recognized the growing popularity of basketball early and had established his tournament to crown a national champion from state and regional champions from around the country. The Hornets accepted with enthusiasm.

In Chicago, Athens fell to Eau Claire HS (Wisconsin), advanced to the consolation finals, and lost on a buzzer beater to Kansas City HS. While disappointed, the Hornets were proud of an historic 1927 season.

The 1928 team returned to the state tournament, beating Bryan, Corsicana, Denton, Waco, and Tyler along the way. At state, Athens bested Beaumont and McKinney to reach the semifinals. Their dream of repeating fell short, however, when they lost 26-23 to eventual state champion Temple. The Hornets settled for third with a win over Dallas Forrest High. The team was still young though, and hungry for more. The year 1929 would be the year of the Hornet.

Chapter 3: "Welcome to Indiana basketball"

The 1929 campaign began with a new Kitts idea, a west Texas basketball trip. The Hornets loaded up into 4 different cars and drove hundreds of miles to defeat El Paso, Lubbock, and other west Texas schools where basketball was on the rise. Upon their return, Athens began another run. Tyler, Corsicana, McKinney, Waco, and Marshall all fell on the way to yet another trip to the state tournament in College Station.

There, Athens advanced to the finals and met Denton High once again, just as in 1927. Hundreds from Athens once again made the trip to cheer on their adopted sons. No telephone was needed this time for those who did not make the trip; Hornets fans back home were able to listen to the game on the radio. The game was tight until the fourth quarter, when the Hornets finally pulled away. Athens 22, Denton 11. The Hornets were state champions again.

Stagg came calling again, and invited Athens to Chicago for the National Tournament. Kitts considered chartering an airplane just two years after Lindbergh, but in the end decided to bus. They did, however, stop by the Lindbergh exhibit in St. Louis on their way. When they arrived, some in the Chicago press were predicting that Athens would win, in part due to “Kitts and his scientific defensive schemes.”

Bartlett Gymnasium on the campus of the University of Chicago was the site of the tournament; the gymnasium still stands today. In Chicago, Athens played the best basketball of the season, and knocked out win after win on the way to the finals. There, they faced Classen High (Oklahoma City), coached by Frank Iba (brother of legendary OSU coach Henry Iba). The game was back and forth until then end, when Athens senior Freddie Tompkins began to put it away at the free throw line.

As the seconds ticked down, the Athens bench became increasingly ecstatic. The clock hit 0:00, and the scoreboard read Athens 25, Classen 21. Little Athens Texas was the #1 team in the country. At the jubilant celebration in Athens which followed the team’s return home, a local speaker pointed out that there were 40,000 high schools in America, and their boys had triumphed over all of them.

Stagg’s national tournament in Chicago had served its purpose. Basketball was thriving as the decade ended. Also, there was increasing skepticism from states and regions about the costs (both money and time away from studies) associated with Stagg’s tournament. As a result, Stagg decided to abandon his pet project after 1930. There would be no more basketball national champion.

The 1930 Hornet team lost a disappointing game to nemesis Denton High in the state tournament. But the 1931 team regrouped. Because of Stagg’s decision to end the Chicago tournament, Coach Kitts came up with a new idea to start the season: a holiday trip to compete against high school teams in the state of Indiana, basketball’s breadbasket.

They left just after Christmas day, and played 10 Indiana teams into early January. Jeffersonville High, Martinsville High, New Albany High, Evansville, Gary, and others. One of those games included a loss to Frankfort High School. 23 years later, Frankfort would become famous for being the last team in 1954 to defeat Milan, before their miracle run towards the state championship and Bobby Plump’s last second shot.

1931, like 1927 and 1929 before, brought home another state championship. Just as in past years, the largest schools in Texas from Dallas, Houston, and Austin all fell to Athens. Only the site of the state tournament celebration was different. In 1931, the Hornets headed for Austin, to compete in the brand new Gregory Gym on the campus of the University of Texas. Athens rolled to the title game, where they defeated Houston San Jacinto 25-22 in overtime. Back home, the town was celebrating their boys once more.

And just like that, it seemed to be all over.

In 1932, one disaster after another hit the Athens basketball community. Their home gym burned to the ground. Six players quit the team due to tensions, only to return later. Rumors began to swirl about Kitts leaving. And Athens began to lose.

That year, Athens lost to Rusk in the district tournament, and failed to make the state tournament for the first time since 1926. At the end of the season, Coach Kitts announced that he had received an opportunity he could not passed up. He had been named head football coach at Rice University. As Kitts arrived in Houston, his first act as coach was to call up his friend Cecil Grigg in Sherman. Grigg was head football coach at Austin College, but was recruited to leave Sherman for Houston. With Grigg by his side, Kitts would lead Rice to the 1934 and 1937 SWC championships in football. Grigg himself would remain at Rice for 35 years and oversee 6 SWC championships during the Owl glory years.

It appeared that the remarkable Athens run was over. But the community went looking for someone to replace Kitts, and they found a Roo. Their run had only just begun.

Chapter 4: "And David put his hand in the bag and took out a stone and slung it. And it struck the Philistine on the head and he fell to the ground. Amen."

John Taylor “Bobo” Nelson had left Sherman after graduation to coach at nearby Mexia. In 1930, Nelson, Kitts, and two other area coaches had recognized a need for an organization to benefit the training and careers of high school coaches, and in a quiet restaurant on a fall night founded the Texas High School Coaches Association (THSCA). Today, this brainchild of a Kangaroo includes nearly 22,000 members.

Nelson was offered the Athens job, and accepted. A strong recommendation from his former Roo coach Pete Cawthon (now at Texas Tech) probably did not hurt. He moved to Athens and immediately began to work. A new gym was built, team unity and discipline were prioritized once again, and exhausting practices under Coach Nelson gave the Hornets endurance they had not yet known. The game of basketball was changing. It was becoming a quicker game, and Nelson was ahead of his peers in recognizing the shifting landscape. Where Kitts had guided Athens to titles with defense, Nelson would lead them with speed.

Nelson was also hired to coach Athens football, and the Hornets had their best season ever. They finally won district, and earned a playoff berth on the road against Greenville High. The game was close, but Greenville edged the Hornets 13-6 in front of a huge hometown crowd. Greenville head coach Henry Frnka, a teammate of Nelson’s at Austin College, would lead the Lions to a state championship one year later. It’s unknown whether the Mason family of Greenville, along with a 1-year-old baby and future Roo named Bob, was in attendance.

The basketball wins in 1933 resumed. Lubbock, El Paso, and Austin High all fell victim. Determined to run with the best, Nelson even scheduled games with SWC freshmen teams. His squad won at Baylor, TCU, and the University of Texas. Athens even traveled to Houston and defeated the Rice freshman team, coached by a Kitts assistant. A district title was won easily, as was another regional title and a trip to state. Like Kitts in 1931, Nelson took his team and much of the town of Athens back to Austin and Gregory Gym. There, they put on the most impressive basketball show in the tournament’s short history.

Athens scored a state record 188 points in its 4 wins at Gregory Gym, an unheard of number for the game in those days. Nobody could keep pace with the Hornets, as they beat El Paso (62-29), Bryan (50-19), Dallas Thomas Jefferson (40-36), and Houston Jefferson Davis (36-20) in the final to win their fourth title in seven years. With most of the squad back in 1934, the Athens community expected a long overdue title defense. They’d get it.

In 1934, the state of Texas kept falling to that little town in Henderson county. Lubbock, Amarillo, Denton, Fort Worth Poly, Dallas Forest High, and a handful of SWC freshman teams yet again all came up short. Another district title, regional title, and trip to Austin were secured. At Gregory Gym, their home away from home, Athens beat Denton (17-12), Houston Jefferson Davis (43-13), and Lamesa (28-22). Coach Nelson had defended his title, and Athens had earned four state championships in eight years.

Chapter 5: "I'll make it"

As basketball increased in popularity, so did the quality of teams at larger schools. Athens had some fine teams, but never threatened for a state title again during the rest of the decade. The larger high schools which had dominated basketball before the Athens run began to do so once again. In 1942, the state of Texas introduced classifications, and the era of small schools competing against the largest schools in the state came to an end.

Nelson remained at Athens until 1941, when he accepted an athletics development position at East Texas State University. His acceptance, however, came with a condition. He insisted that he be allowed to coach as well. For over a decade, Nelson was not only in administration but also an assistant basketball coach for the Lions in Commerce.

Nelson joined forces with Dennis Vinzant, former Tech standout for Pete Cawthon and former Greenville assistant for Henry Frnka. Together, they led East Texas to multiple Lone Star Conference titles and national playoff appearances. Nelson replaced Darrell Tully, who after the war would spend a career as a coach and administrator at Spring Branch ISD in Houston. The stadium used by teams throughout the school district today is named in his honor.

The 1920s and 1930s were the high mark of the Austin College / East Texas State rivalry. As a senior at Austin College, Nelson had helped the Kangaroos defeat East Texas in 1927. But as public universities began to grow dramatically during the Great Depression and after WW2, that rivalry began to wane. East Texas had moved on to the Lone Star conference, composed primarily of state schools. The Kangaroos had played the Lions in basketball nearly every year between 1927 and 1949, and had lost every single time.

But 1949 was different. Austin College had a new home, and AC basketball had two special players.

M.B. Hughey was a Dallas oilman. He was a philanthropist, as was his wife Annie. They both believed in the value of higher education, and decided to give considerable sums in their names. M.B. was a devout Presbyterian; Annie, however, was Methodist. In the end, they compromised. 50% of their gift would go to Nelson’s Austin College and 50% would go to Kitts’s SMU. The AC donation was used to build a new gymnasium in Sherman. The brand new, state-of-the-art Hughey Gymnasium replaced the old Cawthon gym and opened in the fall of 1949.

The 1949-50 Roos were a veteran squad led by senior forward Ralph “Slats” McCord. Coach Byron Gilbreath needed just one missing piece of the puzzle, and he was convinced he had found it in a quick sophomore guard from Greenville by the name of Bob Mason. Coach Nelson and East Texas traveled to Sherman in the fall of 1949 expecting a victory just like the ones earned over the past 22 years. But this time would be different.

Mason and McCord led the Roos to a big halftime lead. Nelson and East Texas attempted to mount a comeback, but it was too little too late. Austin College held on for a 49-41 victory over the Lions, its first victory over that school in Commerce since the last year of Bobo Nelson and Pete Cawthon.

It was the first win for Austin College at Hughey Gym.

McCord graduated in 1950, but the Mason-led Roos were back in 1950-51 with loftier goals. They went on a tear all season along, and won the Texas Conference championship. It was Austin College’s first basketball conference championship in 29 years, just before the arrival in Sherman of Coach Nelson.

Bob Mason and Ralph “Slats” McCord spent decades at Austin College in coaching and administration. They are both worthy of their own tales one day. Mason passed unexpectedly in 1999, and McCord passed in 2012. Both Kangaroo legends have been inducted into the AC Hall of Honor.

After years in Commerce, Nelson retired and returned to his home town of Celina. There, he assisted with football and basketball coaching duties for free, so that tiny Celina and its small budget could have an athletics program. He passed in 1964, and was inducted into the AC Hall of Honor in 1966.

If Coach Nelson could only see Celina today.

It’s Homecoming weekend in Sherman, and your humble author plans to attend his 25th reunion. If Bobo Nelson has taught us anything, with his round trip from little Celina to Athens and back, it’s that you can go home again.

Hope to see or meet a lot of you in Sherman. Go Roos.

Wait, what? Waco?

Yes, Waco. Before TCU’s move to Fort Worth in 1910, the school was located in Waco, TX. West Waco to be exact. East Waco was the home of their rival Baylor. The "Revivalry" was initially an all-McLennan County affair.

One month later, TCU made the short trip east to take on the Bears during Thanksgiving week. Baylor furnished special trains to bring thousands of alumni back to campus. Parades were organized. The Baylor band performed “The Homecomers March”, and the Bears barely defeated TCU 6-3.

It was the first ever Homecoming in this nation’s history.

It’s Homecoming weekend in Sherman, TX. All of this writing has been something of a Homecoming for me already. I’ve immensely enjoyed meeting many of you both online and in person, and am looking forward to more of the same. I am excited to see many of you on campus this weekend, and if not at some future event. I hope the writing has filled you with the same amount of pride and enjoyment that it has for me.

Today’s Roo Tale was voted on by the Go Roos Facebook group earlier this fall. It’s a Texas Hoosiers tale, about the near impossible things that can be accomplished by smaller schools against their larger competitors. It focuses on the spectacular basketball accomplishments of little Athens, TX, and the Roo who helped to make it happen. It mentions this same Roo’s efforts in establishing a Coaches Association in Texas that now includes tens of thousands of members. And it features supporting actor roles by two AC icons, Coach Ralph “Slats” McCord and Coach Bob Mason.

And it’s a story about coming home. See you at Homecoming.

Chapter 1: "Didn't know they grew 'em so small on the farm"

The relentless northward growth of the Dallas / Fort Worth metroplex over the past 100 years has transformed small towns in Collin County into bustling cities in their own right. Little Celina, TX is no different. The town of a few hundred residents was not even incorporated when little John Taylor Nelson was born in 1905.

Nelson was a standout athlete at Celina High School. He participated in football, baseball, and track. But his first love was basketball. As luck would have it, Celina was a basketball town. Nelson helped guide Celina to the state tournament in the early 1920s, and revenue from the sport actually assisted the early days of Celina football.

Celina lies halfway between Austin College and SMU, and Nelson’s high school days coincided with the height of the Kangaroo-Mustang rivalry. AC beat SMU three out of four times in football while Nelson competed for Celina, and the Roos beat the Mustangs in basketball his senior year of 1923.

Although still young, Dallas was quickly propelling SMU towards athletic success by luring some of the best athletes in the state. The Mustangs’ first star was a local boy named Jimmy Kitts. At SMU, Kitts excelled in football, baseball, and basketball, and earned All-American honors. Kitts was the SMU QB when his Mustangs fell to AC 17-7 at Fair Park Stadium in 1921. His career included more than a few trips to Sherman, and many of those contests were attended by Nelson himself.

Because of the influence of Kitts, Nelson considered SMU in 1923. However, AC had just hired the already well known Pete Cawthon, coach at Terrill Prep (now St. Mark’s) in Dallas. Cawthon’s Terrill boys were committed to following their coach to Sherman, and the idea of being a part of something new and exciting was too much. Nelson decided he would join them and become a Roo. As Nelson headed to Grayson county instead of Dallas county, his Celina teammates held a party to wish John Taylor well. Nobody called him John Taylor though. Everyone referred to him by his old Celina nickname: “Bobo”.

At Sherman, Bobo Nelson was a four sport star. He was a member of Cawthon’s 1923 TIAA championship team, and was a contributor in AC’s 7-3 upset of Baylor in Waco. He starred on the diamond, and was a speedster on the track. But his main contributions to AC athletics were on the basketball court.

The golden era of AC athletics in the 1920s included basketball. Nelson and the 1924 Roos had a strong season, defeating SMU, TCU, and eventual TIAA champion Southwestern. He was a starter all four years. In his senior season of 1927, the Roos made a run at the TIAA title and fell just short. That same year, AC defeated East Texas State down the road in Commerce. It was a victory over an Austin College rival that would not be seen again for decades.

While Nelson was shining against schools like SMU, Mustang Jimmy Kitts had moved on to coaching at the University of Dallas. There, he became friends with arguably the most famous Roo athlete of all, Cecil Grigg. Grigg had ties with the University of Dallas after his AC playing days, and at the time was an NFL star alongside Jim Thorpe with the Canton Bulldogs. Kitts persuaded Grigg and fellow professionals to participate in a football game exhibition with the University of Dallas in downtown Dallas. As reported by the Post, "Jimmy Kitts, former SMU captain, and Cecil Grigg, who is perhaps the greatest athlete Austin College ever produced, played vigorous football."

The two became close friends because of the experience, and would be reunited later. For Jimmy Kitts, there would be no escaping the influence of that school in Sherman.

Chapter 2: "I'm sure going to the state finals is beyond your wildest dreams, so let's just keep it right there."

High school football exploded in popularity in East Texas during the 1920s. Every town from Dallas to the Sabine river dreamed of gridiron glory, and many achieved it. Tyler, Marshall, and Corsicana became famous for their success.

But little Athens, TX struggled. Try as they might, the Athens Hornets consistently failed to make the playoffs. When that goal was accomplished, Athens nemesis Marshall was always there to send the Hornets home for good.

Athens never stopped trying to overcome that hurdle. But like a wise investor deciding not to put all of one’s eggs into the same basket, the Henderson county town also began to dedicate itself to a different sport.

As the 1920s progressed, basketball became the sport of choice around which the Athens community gathered. Families of players from rural Henderson county were encouraged to move into town. Youngsters were as likely to practice their free throws as they were to put on a leather helmet. And Athens was focused on landing a star coach that would lead them to glory in the gymnasium that had eluded them on the football field.

The population of Athens was roughly 3,000 in 1920. Dallas, Houston, & Austin were well over 100,000. Even mid-sized towns such as Waco were over 10 times the size of Athens. At that time, all 200+ schools in the state of Texas completed in one classification, Class A, for a state championship in football, basketball and baseball.

For a small school to win a championship, something along the lines of a Milan miracle would be necessary. Tiny Milan High School won the Indiana High School state championship in 1954, and became the inspiration for the movie “Hoosiers”. In 1925, Athens believed they had found their version of Hoosier Coach Norman Dale. Jimmie Kitts was lured away from the University of Dallas to coach the sport he loved.

Basketball in the 1920s was different compared to today. It was slower and shorter. The game clock never stopped, and there was no shot clock. The games lasted for only four 10-minute quarters, and there was no 10-second midcourt rule. Low scores were common, as was stalling. Kitts was an innovator who refined the game in Athens. Hook shots were introduced on the offensive side; double teams were a new feature on defense. The 1925 Athens team showed immediate promise under Kitts, and the 1926 team was a state power. There was excitement and anticipation in 1927.

Nacogdoches fell on the way to a district championship. Athens cruised through regionals, defeating Huntsville and earning a trip to the state tournament. Because of construction in Austin, the state tournament was held at DeWare Field House in College Station. There, Athens rolled up wins against Shiner and Cisco to reach the finals against Denton High School.

Hundreds traveled to College Station to watch the game. Those who could not make the trip were kept up-to-date via the telephone. Down by two points at the half, star Jake Reynolds and the Hornets came out firing and coasted to a 23-14 win. Little Athens Texas was the best basketball team in the state. The team arrived back home in Athens for a celebration at the courthouse.

Before departing for home, Kitts received a telegram. His Hornets had been invited to play in Amos Alonzo Stagg’s National High School basketball tournament in Chicago later that spring. Stagg, famous for his late 1890s Chicago Maroons football teams, had recognized the growing popularity of basketball early and had established his tournament to crown a national champion from state and regional champions from around the country. The Hornets accepted with enthusiasm.

In Chicago, Athens fell to Eau Claire HS (Wisconsin), advanced to the consolation finals, and lost on a buzzer beater to Kansas City HS. While disappointed, the Hornets were proud of an historic 1927 season.

The 1928 team returned to the state tournament, beating Bryan, Corsicana, Denton, Waco, and Tyler along the way. At state, Athens bested Beaumont and McKinney to reach the semifinals. Their dream of repeating fell short, however, when they lost 26-23 to eventual state champion Temple. The Hornets settled for third with a win over Dallas Forrest High. The team was still young though, and hungry for more. The year 1929 would be the year of the Hornet.

Chapter 3: "Welcome to Indiana basketball"

The 1929 campaign began with a new Kitts idea, a west Texas basketball trip. The Hornets loaded up into 4 different cars and drove hundreds of miles to defeat El Paso, Lubbock, and other west Texas schools where basketball was on the rise. Upon their return, Athens began another run. Tyler, Corsicana, McKinney, Waco, and Marshall all fell on the way to yet another trip to the state tournament in College Station.

There, Athens advanced to the finals and met Denton High once again, just as in 1927. Hundreds from Athens once again made the trip to cheer on their adopted sons. No telephone was needed this time for those who did not make the trip; Hornets fans back home were able to listen to the game on the radio. The game was tight until the fourth quarter, when the Hornets finally pulled away. Athens 22, Denton 11. The Hornets were state champions again.

Stagg came calling again, and invited Athens to Chicago for the National Tournament. Kitts considered chartering an airplane just two years after Lindbergh, but in the end decided to bus. They did, however, stop by the Lindbergh exhibit in St. Louis on their way. When they arrived, some in the Chicago press were predicting that Athens would win, in part due to “Kitts and his scientific defensive schemes.”

Bartlett Gymnasium on the campus of the University of Chicago was the site of the tournament; the gymnasium still stands today. In Chicago, Athens played the best basketball of the season, and knocked out win after win on the way to the finals. There, they faced Classen High (Oklahoma City), coached by Frank Iba (brother of legendary OSU coach Henry Iba). The game was back and forth until then end, when Athens senior Freddie Tompkins began to put it away at the free throw line.

As the seconds ticked down, the Athens bench became increasingly ecstatic. The clock hit 0:00, and the scoreboard read Athens 25, Classen 21. Little Athens Texas was the #1 team in the country. At the jubilant celebration in Athens which followed the team’s return home, a local speaker pointed out that there were 40,000 high schools in America, and their boys had triumphed over all of them.

Stagg’s national tournament in Chicago had served its purpose. Basketball was thriving as the decade ended. Also, there was increasing skepticism from states and regions about the costs (both money and time away from studies) associated with Stagg’s tournament. As a result, Stagg decided to abandon his pet project after 1930. There would be no more basketball national champion.

The 1930 Hornet team lost a disappointing game to nemesis Denton High in the state tournament. But the 1931 team regrouped. Because of Stagg’s decision to end the Chicago tournament, Coach Kitts came up with a new idea to start the season: a holiday trip to compete against high school teams in the state of Indiana, basketball’s breadbasket.

They left just after Christmas day, and played 10 Indiana teams into early January. Jeffersonville High, Martinsville High, New Albany High, Evansville, Gary, and others. One of those games included a loss to Frankfort High School. 23 years later, Frankfort would become famous for being the last team in 1954 to defeat Milan, before their miracle run towards the state championship and Bobby Plump’s last second shot.

1931, like 1927 and 1929 before, brought home another state championship. Just as in past years, the largest schools in Texas from Dallas, Houston, and Austin all fell to Athens. Only the site of the state tournament celebration was different. In 1931, the Hornets headed for Austin, to compete in the brand new Gregory Gym on the campus of the University of Texas. Athens rolled to the title game, where they defeated Houston San Jacinto 25-22 in overtime. Back home, the town was celebrating their boys once more.

And just like that, it seemed to be all over.

In 1932, one disaster after another hit the Athens basketball community. Their home gym burned to the ground. Six players quit the team due to tensions, only to return later. Rumors began to swirl about Kitts leaving. And Athens began to lose.

That year, Athens lost to Rusk in the district tournament, and failed to make the state tournament for the first time since 1926. At the end of the season, Coach Kitts announced that he had received an opportunity he could not passed up. He had been named head football coach at Rice University. As Kitts arrived in Houston, his first act as coach was to call up his friend Cecil Grigg in Sherman. Grigg was head football coach at Austin College, but was recruited to leave Sherman for Houston. With Grigg by his side, Kitts would lead Rice to the 1934 and 1937 SWC championships in football. Grigg himself would remain at Rice for 35 years and oversee 6 SWC championships during the Owl glory years.

It appeared that the remarkable Athens run was over. But the community went looking for someone to replace Kitts, and they found a Roo. Their run had only just begun.

Chapter 4: "And David put his hand in the bag and took out a stone and slung it. And it struck the Philistine on the head and he fell to the ground. Amen."

John Taylor “Bobo” Nelson had left Sherman after graduation to coach at nearby Mexia. In 1930, Nelson, Kitts, and two other area coaches had recognized a need for an organization to benefit the training and careers of high school coaches, and in a quiet restaurant on a fall night founded the Texas High School Coaches Association (THSCA). Today, this brainchild of a Kangaroo includes nearly 22,000 members.

Nelson was offered the Athens job, and accepted. A strong recommendation from his former Roo coach Pete Cawthon (now at Texas Tech) probably did not hurt. He moved to Athens and immediately began to work. A new gym was built, team unity and discipline were prioritized once again, and exhausting practices under Coach Nelson gave the Hornets endurance they had not yet known. The game of basketball was changing. It was becoming a quicker game, and Nelson was ahead of his peers in recognizing the shifting landscape. Where Kitts had guided Athens to titles with defense, Nelson would lead them with speed.

Nelson was also hired to coach Athens football, and the Hornets had their best season ever. They finally won district, and earned a playoff berth on the road against Greenville High. The game was close, but Greenville edged the Hornets 13-6 in front of a huge hometown crowd. Greenville head coach Henry Frnka, a teammate of Nelson’s at Austin College, would lead the Lions to a state championship one year later. It’s unknown whether the Mason family of Greenville, along with a 1-year-old baby and future Roo named Bob, was in attendance.

The basketball wins in 1933 resumed. Lubbock, El Paso, and Austin High all fell victim. Determined to run with the best, Nelson even scheduled games with SWC freshmen teams. His squad won at Baylor, TCU, and the University of Texas. Athens even traveled to Houston and defeated the Rice freshman team, coached by a Kitts assistant. A district title was won easily, as was another regional title and a trip to state. Like Kitts in 1931, Nelson took his team and much of the town of Athens back to Austin and Gregory Gym. There, they put on the most impressive basketball show in the tournament’s short history.

Athens scored a state record 188 points in its 4 wins at Gregory Gym, an unheard of number for the game in those days. Nobody could keep pace with the Hornets, as they beat El Paso (62-29), Bryan (50-19), Dallas Thomas Jefferson (40-36), and Houston Jefferson Davis (36-20) in the final to win their fourth title in seven years. With most of the squad back in 1934, the Athens community expected a long overdue title defense. They’d get it.

In 1934, the state of Texas kept falling to that little town in Henderson county. Lubbock, Amarillo, Denton, Fort Worth Poly, Dallas Forest High, and a handful of SWC freshman teams yet again all came up short. Another district title, regional title, and trip to Austin were secured. At Gregory Gym, their home away from home, Athens beat Denton (17-12), Houston Jefferson Davis (43-13), and Lamesa (28-22). Coach Nelson had defended his title, and Athens had earned four state championships in eight years.

Chapter 5: "I'll make it"

As basketball increased in popularity, so did the quality of teams at larger schools. Athens had some fine teams, but never threatened for a state title again during the rest of the decade. The larger high schools which had dominated basketball before the Athens run began to do so once again. In 1942, the state of Texas introduced classifications, and the era of small schools competing against the largest schools in the state came to an end.

Nelson remained at Athens until 1941, when he accepted an athletics development position at East Texas State University. His acceptance, however, came with a condition. He insisted that he be allowed to coach as well. For over a decade, Nelson was not only in administration but also an assistant basketball coach for the Lions in Commerce.

Nelson joined forces with Dennis Vinzant, former Tech standout for Pete Cawthon and former Greenville assistant for Henry Frnka. Together, they led East Texas to multiple Lone Star Conference titles and national playoff appearances. Nelson replaced Darrell Tully, who after the war would spend a career as a coach and administrator at Spring Branch ISD in Houston. The stadium used by teams throughout the school district today is named in his honor.

The 1920s and 1930s were the high mark of the Austin College / East Texas State rivalry. As a senior at Austin College, Nelson had helped the Kangaroos defeat East Texas in 1927. But as public universities began to grow dramatically during the Great Depression and after WW2, that rivalry began to wane. East Texas had moved on to the Lone Star conference, composed primarily of state schools. The Kangaroos had played the Lions in basketball nearly every year between 1927 and 1949, and had lost every single time.

But 1949 was different. Austin College had a new home, and AC basketball had two special players.

M.B. Hughey was a Dallas oilman. He was a philanthropist, as was his wife Annie. They both believed in the value of higher education, and decided to give considerable sums in their names. M.B. was a devout Presbyterian; Annie, however, was Methodist. In the end, they compromised. 50% of their gift would go to Nelson’s Austin College and 50% would go to Kitts’s SMU. The AC donation was used to build a new gymnasium in Sherman. The brand new, state-of-the-art Hughey Gymnasium replaced the old Cawthon gym and opened in the fall of 1949.

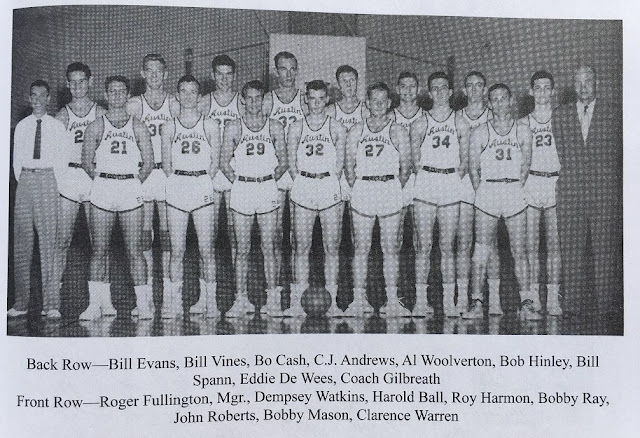

The 1949-50 Roos were a veteran squad led by senior forward Ralph “Slats” McCord. Coach Byron Gilbreath needed just one missing piece of the puzzle, and he was convinced he had found it in a quick sophomore guard from Greenville by the name of Bob Mason. Coach Nelson and East Texas traveled to Sherman in the fall of 1949 expecting a victory just like the ones earned over the past 22 years. But this time would be different.

Mason and McCord led the Roos to a big halftime lead. Nelson and East Texas attempted to mount a comeback, but it was too little too late. Austin College held on for a 49-41 victory over the Lions, its first victory over that school in Commerce since the last year of Bobo Nelson and Pete Cawthon.

It was the first win for Austin College at Hughey Gym.

McCord graduated in 1950, but the Mason-led Roos were back in 1950-51 with loftier goals. They went on a tear all season along, and won the Texas Conference championship. It was Austin College’s first basketball conference championship in 29 years, just before the arrival in Sherman of Coach Nelson.

Bob Mason and Ralph “Slats” McCord spent decades at Austin College in coaching and administration. They are both worthy of their own tales one day. Mason passed unexpectedly in 1999, and McCord passed in 2012. Both Kangaroo legends have been inducted into the AC Hall of Honor.

After years in Commerce, Nelson retired and returned to his home town of Celina. There, he assisted with football and basketball coaching duties for free, so that tiny Celina and its small budget could have an athletics program. He passed in 1964, and was inducted into the AC Hall of Honor in 1966.

If Coach Nelson could only see Celina today.

It’s Homecoming weekend in Sherman, and your humble author plans to attend his 25th reunion. If Bobo Nelson has taught us anything, with his round trip from little Celina to Athens and back, it’s that you can go home again.

Hope to see or meet a lot of you in Sherman. Go Roos.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)